The Pristophone and its companion the Bass Pristophone have been the primary focus of my work with experimental instruments, the product of nearly a thousand hours of work beginning in 2007. I’ve built eight iterations of the instruments, completing the final version in 2017, though I am still constantly making improvements.

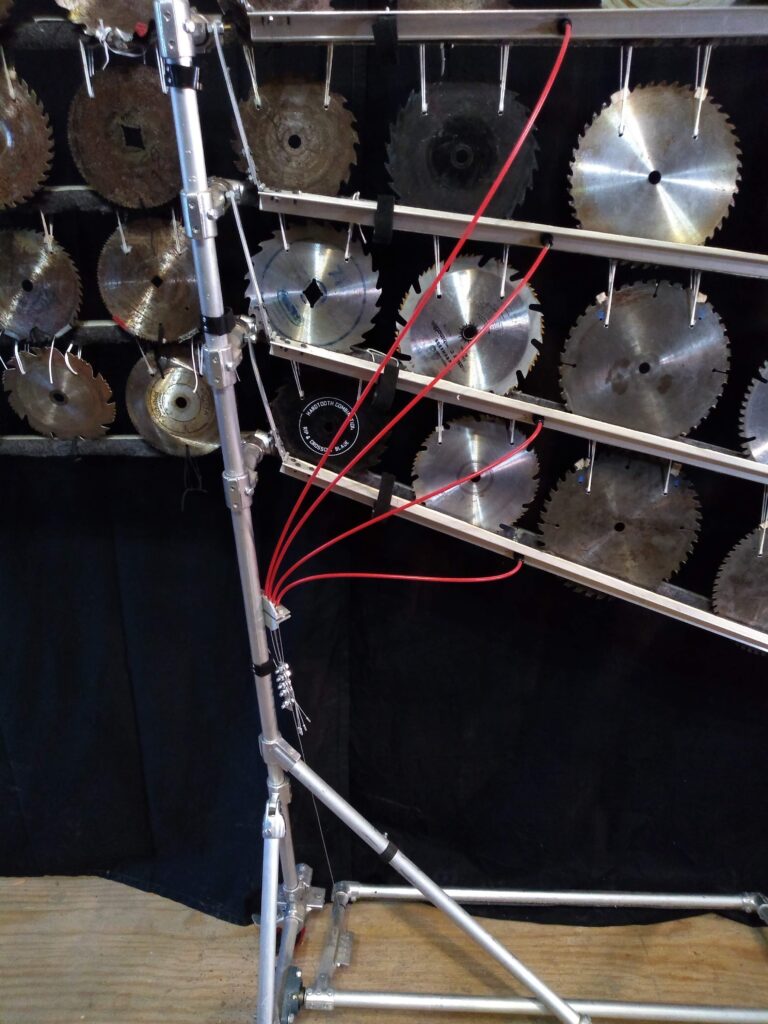

The sound of the instrument comes from pitched circular saw blades. Nearly all of them have been recycled from previous lives in service of clearing forests, processing lumber, and building houses, possibly on those same cleared forests. Destructive implements are transformed into creative elements. I choose used blades for another very practical reason; it’s been necessary to search through hundreds of saws created over many decades, rather than work with the limited variety commercially available today, in order to find blades that have an appropriate timbre over a broad pitch range.

There are 65 blades total, 14 in the bass instrument and 51 in the treble. The full range is A1-C#7. Bb2 is doubled for convenience. The Pristophone is 11 feet long and eight feet tall. The Bass is 14 feet long and seven feet tall. Because of this, playing the instrument becomes a physical performance. Composition is choreography. Sound is space. Much of my inspiration comes from the instruments, music, and philosophy of Harry Partch. I’ve borrowed his concept of corporeality, the idea that music should reflect and be reflected by the physicality of the human body.

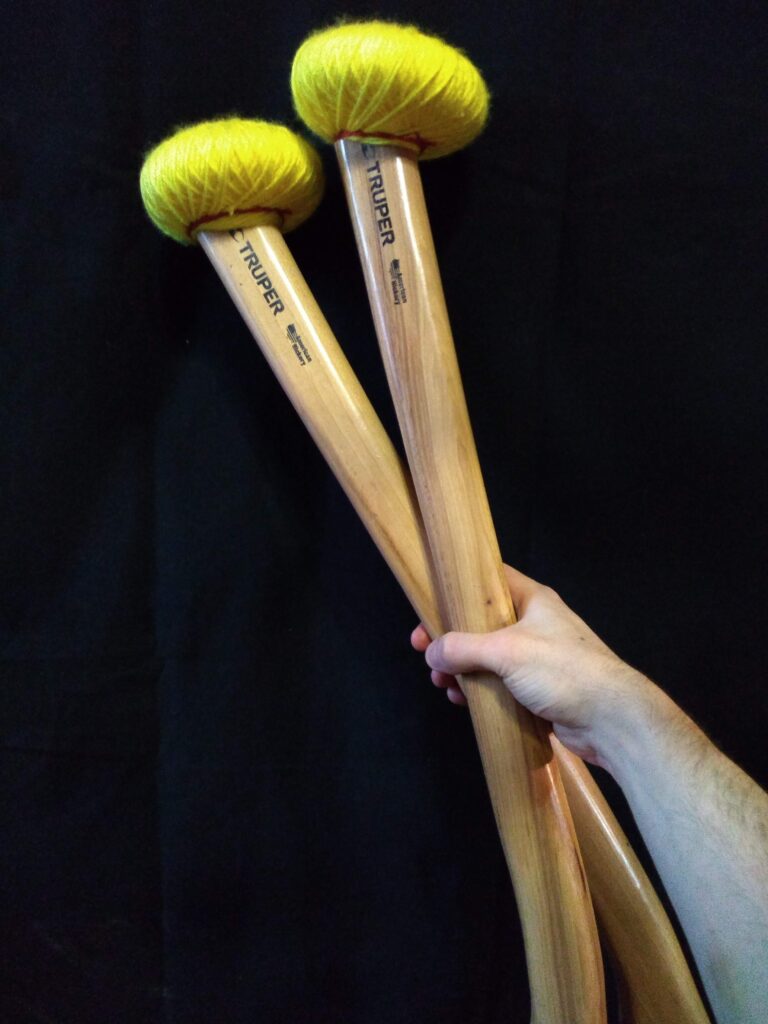

I didn’t, however, use Partch’s 43-note just intonation tuning system. The Pristophone is tuned to the standard 12-tone equal temperament. I believe this suits the communal nature of music. The Pristophone can easily fit in with any contemporary classical instrument. Similarly, my goal has been to allow the facility of performance and the acoustical nuance of other popular instruments. The tone ranges from gently dulcet to piercingly abrasive, dry to sustained, imperceptibly soft to painfully loud. It is capable of a variety of extended techniques: different mallets and implements, buzzing sounds, playing harmonics, hand muting, and bowing.

The Pristophone arose out of a deliberate attempt to find new sounds. I believe in using the unfamiliar to shake the listener’s expectations and get closer to the primordial roots of music. Expected elements make it too easy to intellectualize art. But unexpected voices redirect our attention to the qualities of sound itself, making it easier to recognize the prehistoric origins of musical expression. We are allowed a better connection to our physical bodies and our metaphysical higher selves.

In 2007 I became fascinated with the pile of discarded projects from the introductory welding class in the arts department at UW-Madison. I extended my exploration with metallphones that summer, trolling garage sales in my hometown. In a local sawmill employee’s garage I found two stacks of 12” blades. I bought one of each type. A few weeks later I found 30 more at a resale shop, which I bargained down to 75¢ each.

As I experimented with the blades I made a series of discoveries that suggested the possibility that they could be formed into a singular instrument. First I found how to suspend them, rather than simply setting them on foam, in order to get the sense of a pitch. A few months later I learned how to drill holes through hardened steel, two per blade, allowing me to hang them in rows. I found that drilling them 30% of the distance between the edge and the arbor hole gave the best sense of pitch, by encouraging the resonance of harmonics that approximated the standard harmonic series while dampening those harmonics that conflicted with it. I tried out different rack systems, first by commandeering the gong racks from the Percussion Department, and later by building my own version out of lumber.

A few years later I discovered that blades are tunable. Observing the steel pans (steel drums) that another student was practicing, I decided to use roughly the same tuning method on a spare saw, blocking the edges of the blade with scraps of wood while hammering in the center, making the metal plate very slightly bell-shaped and thus raising the pitch. This was an immense development that suggested the potential of building a finely tuned instrument. I began earnestly searching Madison for any blades I could find, placing wanted-to-buy Craigslist ads and biking all over Dane County in pursuit of more saws. The instrument was more than three octaves by the end of my academic career, though there were many missing pitches in that range.

Following college I sought new outlets for musical expression, with a particular interest in music’s political power. I became involved with Forward! Marching Band, a radically inclusive brass band that conglomerated from musicians who brought their instruments to the 2011 protests against Wisconsin governor Scott Walker. I was initially on snare drum, then switched to trombone. After a year away from Madison, I moved back to the area in 2012. I synthesized my two major interests by building the first Marching Pristophone to use with F!MB. Not having much income, I fashioned a portable rack and carrying harness from old ski poles, an Army surplus ALICE pack, and parts from a walker.

The limitation of space on the marching rack led me to develop my current system of pitch organization. The twelve pitches in an octave were set in a block, four rows high and three columns wide. Going up one row means going up one half step. One row over is a major third, and three rows over is an octave. In addition to saving space, this system enabled easy playing of triadic harmony. A major chord in close position is made up of a major third (one row to the right), a minor third (down and to the right), and a perfect fourth (up and to the right). The symmetry of the system means that playing different chords involves shifting the same shape up, down, or over.

In 2014 I moved to a new job in Chicago. I got caught up with Environmental Encroachment, a brass band I had encountered years before at festivals I attended with F!MB. I built the second iteration of the Marching Pristophone, trying aluminum tubing as a construction material. This version was an octave higher than the previous one, with an additional four blades. Most importantly, I built it so that it could be broken down to travel on trains. The device I made to transport it wasn’t that graceful. It was an ad hoc assemblage of a plank, a caster, a dowel, and a large tarpaulin wrapped around it all. I built it in a few hours before my first rehearsal, and never got around to building a nicer looking transportation device for this version.

My job gave me the ability to finally buy all the parts I needed to complete the full-sized Pristophone I had been planning for years. My friend Jeff Strong graciously set me up with a workshop in his attic, my base of operations for the last several years. I laid out all 65 blades and began fitting together piles of aluminum rack material around them.

There were many challenges in building the final version of the Pristophone. It had to be ergonomic, each blade close as possible to the others and easily reachable from a standing position. It had to be durable. It had to be movable. I needed to be able to assemble or disassemble the entire Pristophone and Bass Pristophone in an hour, and all the parts had to fit in the back of a van or SUV. The Marching Pristophone had to be a detachable element so that I could still play it with EE. I needed a damper pedal that could simultaneously stop vibrations on the bottom 2.5 octaves of the instrument.

I began by rebuilding the marching instrument in a way that could be incorporated into the larger set, even though I had built the last marching instrument only a year earlier. My expectations for this version were greater. I needed to set it up or tear it down in less than 15 minutes. It needed to travel in a way that did not compress the blades and potentially detune them. Most difficult was that I wanted it to become a bike trailer.

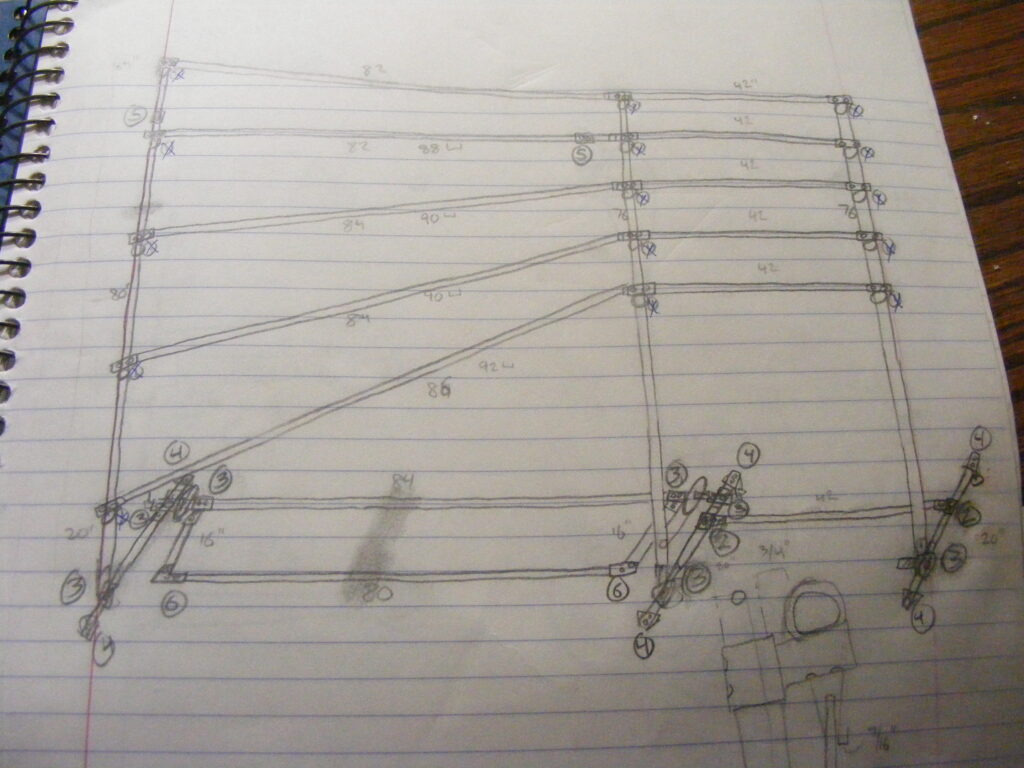

I used ¾” aluminum tubing (which is actually 1.08” wide), aluminum L channeling, and detachable Speed-Rail fittings. The rack consisted of five rails. Four rails were for the four rows of saws. The fifth rail on the bottom was used to attach elastic bands to the lowest row of blades so they wouldn’t swing excessively. These five rails detached from each other and folded accordion-style. The vertical tubing sections at the ends of the rows were clamped between four sections of L channeling, with two sections on each end. A channel on the bottom was equipped with two 12” balloon tires, like those on a handtruck. A channel on the top had two handles. I used vinyl fabric, batting, and a zipper to create a waterproof jacket that would slip around the assemblage and keep the saws from rattling when going over bumps. The handles can be removed and replaced with a long arm that attaches the instrument to the chainstays of a bike. The arm doubles as a leaf spring, protecting the instrument when going over Chicago’s infamous potholes.

The lower saws of the treble instrument became their own unit to which the marching instrument could attach. Because the marching saws were all roughly the same diameter, the rails for it were parallel. But this wasn’t possible with the broad range of sizes in the bottom 2.5 octaves, going from 18 inches to 6. Therefore, at the far left end of the instrument the lowest blades start one foot from the floor and extend upward seven feet. At the right end of the main body, the saws converge until they are the same height as the marching instrument. The fittings at this juncture have been modified to accommodate the irregular angles of the rails on the left side. Looking from the side, one can see that these rails form a warped plane, because the upright posts angle back at different degrees. This is because each rail extends about an inch, on the z axis, behind the one below, providing space for the damper system, and the height difference between the blades is much greater on the left.

This is intended to be my final build of the Pristophone, so I wanted to make it as durable as possible. I used aluminum for all rails and fittings because, as George Costanza’s father has said, aluminum has the best strength-to-weight ratio. This metal was also simple to machine with various saws, grinders, and taps. The Speed Rail fittings are great for quick disassembly, but they are too wobbly for permanent fixtures. Therefore, most of the junctures are solidified with one or two machine bolts. Especially sensitive connections, such as those between the upright posts and the bottom crossbars, are reinforced with triangular bracing.

Every instrument has its own strengths and weaknesses concerning playability, and the Pristophone is no different. I’ve made every effort to make playing the instrument more ergonomic and mitigating its particular challenges. The greatest difficulty in playing the instrument is navigating space, covering the distance from one note to the next. I’ve accounted for this through my unique pitch organization system, which places blades as close to each other as possible. Vertically, blades come as close as possible to touching. Horizontally, I try to leave the smallest gap possible so that blades will not touch each other, even when they sometimes move side to side when struck. All of the smaller blades are restrained by an elastic loop at the bottom to limit how far they can move when they are hit especially hard. This prevents blades from swinging wildly, keeping them ready in place for the next note. Moving quickly from one note to the next can be a challenge, given the amount of lateral distance the mallets must cover and the small target they must strike; to have a clear pitch the blades must be hit very close to center. To counteract this, I generally play with four mallets. I use the vibraphone grip developed by Gary Burton, rotated upward 90 degrees.

One limitation I found with earlier versions of the instrument was the extreme resonance of the blades. Many of them produce sound more than thirty seconds after they are struck. Imagine a piano with the sostenuto pedal permanently engaged, or a drum solo in a cathedral. Each note was engulfed by the preceding notes. To make the instrument a bit more practical, I included a damper system. This was the most challenging part to design. The damper bars were to clamp down simultaneously on 28 blades with enough force to stop them from ringing within one second. This is still more than ten times the decay of a piano or vibraphone with the pedal up, but saw blades, many of them weighing several pounds, contain much more kinetic energy than a piano string. The damper system was to be operated by a pedal, which could require only a moderate amount of force. The blades were to vibrate freely with the pedal up, but be silenced without too much downward travel of the pedal. The entire system was to be nearly frictionless and silent. And, like the rest of the instrument, the damper system had to disassemble quickly.

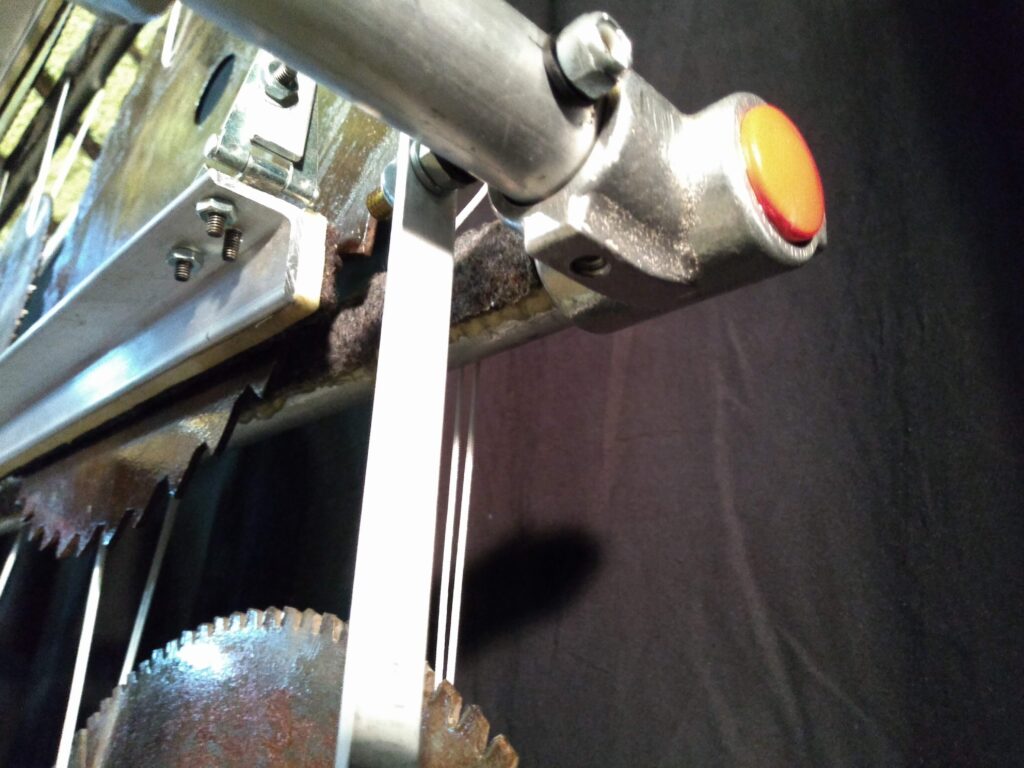

I started out with four long sections of one-inch aluminum L channeling. These were placed directly opposite the rails, so that they could clamp against them. I lined the surface with a layer of ¼” thick foam, covered by 1/8” strip of natural wool insulation strip. This last element wasn’t cheap, but it was the best product I could find that was durable while providing instant damping without buzzing. The rails were lined with the wool strip only, which kept the blade close enough to the rail that there was little risk of mallet shafts striking the rail.

I suspended the bars from the upright support posts on both sides. Each bar had an aluminum strip attached to each side via a hinge. The top of the aluminum strips end with a brass rod. The unthreaded portion of the rod passes through nylon bushings within the upright post. The outer end of the brass rod is retained by a lock nut, screwed on finger-tight.

I had always planned on using cables to pull the damper bars closed, but all my initial designs had the cables passing through the center rails, toward the player, and being redirected by a complicated series of pulleys before they connected directly to the pedal. As best I tried, I could not make it work in my mind. I imagined the cables slipping off the pulleys or getting tangled up with the mallets. I thought of the noise and friction of steel abrading aluminum, of the synchronous movement of dozens of delicate elements, of the difficulty of taking it all apart. Eventually—and I don’t know why it took so long—I imagined a much simpler way to push the damper bars forward from the back side. It involved bicycle cables and housing, in a system very similar to a bike brake lever. Eight cable housings were fixed in place between the sides of each bar and the upright posts. The cables were attached to both the pedal and the rails. As the pedal was pushed down, the length of cable between the pedal and post increased, and the length of cable between the bar and rail decreased by the same amount. I included bike brake cable adjustment screws where the housing connected to the damper bars, so that I could make fine timing adjustments to the system.

I liked the way the organic curve of the cables contrasted with the sharp angles of the frame. The fluidity of the system and the way that metal was forced through the housing reminded me of arteries, so I chose to purchase crimson housing, matching the red casters and tubing end plugs. Interestingly, when I met my partner Vesna I would see similar themes in her own work: the relationships between humanity, biology, and the artificial world.

The Pristophone breaks down into fourteen sections, each 5-8 feet long. There are five rails, four damper bars, three upright posts, and one crossbar. The marching section becomes its own unit. Eventually the four rails that have saws attached will pack into a single case. The Bass Pristophone has ten large sections: six rails and four posts. The fourteen bass saws are carried separately, though I have plans for a better system for moving them.

Thirteen years is a long time to spend on any project, and progress has been gradual. I’ve done what I can, as time and money allows. In the near future of late 2019 I will be restructuring my schedule to give me several days a week in the studio. I will be focusing on an ongoing project of arranging and recording Erik Satie’s piano works for the Pristophone, to be released in 2020. The music is broken into different tracks, between three and fourteen per piece, and each track must be memorized. I will be focusing on composing new works for the instrument. And as always, there are improvements to be made. In the next year I will retune and paint the instrument and build carrying cases.